As a programmer there's no greater joy than trying to code my way out of little daily annoyances. Lately I've been annoyed by GitHub's UI and I set up to fix this using Gleam and a little Raspberry Pi Zero.

The problem

I work a lot on the Gleam compiler, it's quite common for me to have many open PRs waiting to be reviewed and merged. One thing that usually happens is one of them (or some other PR) is merged and then conflicts start popping up without me noticing, until the reviewer pings me asking for a rebase.

The thing that's been bugging me for a while is that GitHub's PR view is not showing me the mergeability of any of my open PRs: that is wether they have conflicts I need to address, or if they don't need any of my attention.

Whenever a PR is merged I need to go check each of the remaining ones individually and see if there's a conflict or not. I find that quite annoying!

The solution

GitHub has a handy GraphQL API. I had used it a couple of times to write small scripts, and so I was pretty confident it could help me solve this problem. I don't need to fetch a lot of data: for each PR I need to know its title, a url pointing to it, whether it is mergeable, and if it is a draft. The GraphQL query I ended up writing looks like this:

query {

viewer {

pullRequests(first: 50, states: OPEN, orderBy: { field: UPDATED_AT, direction: DESC }) {

nodes {

title

url

mergeable

isDraft

}

}

}

}

So how do we query the GitHub GraphQL API using Gleam? We can craft an HTTP request with the proper headers and body as suggested by GitHub's own documentation:

The endpoint is

https://api.github.com/graphqlIt needs to be a POST request…

…with a json body containing a

"query"string fieldand an

"authorization"header with a suitable GitHub token

Building such request in Gleam can look something like this, using the gleam_http package:

import gleam/http

import gleam/http/request

pub fn fetch_pull_requests(gh_token: String) {

let query = "the GraphQL query I showed you earlier"

let request =

request.new()

// It's a POST request

|> request.set_method(http.Post)

// For the `api.github.com/graphql` endpoint

|> request.set_host("api.github.com")

|> request.set_path("/graphql")

// With an authorization header

|> request.prepend_header("authorization", "bearer " <> gh_token)

// And a json body containing a `"query"` string field

|> request.set_body("{ \"query\": \"" <> query <> "\"}")

}

And we're good to go, now we have to actually send the request and see what the server replies with. We're using the gleam_httpc client to do that:

import gleam/http

import gleam/http/request

+import gleam/httpc

pub fn fetch_pull_requests(gh_token: String) {

let query = "the GraphQL query I showed you earlier"

- let request =

+ let assert Ok(response) =

request.new()

|> request.set_method(http.Post)

|> request.set_host("api.github.com")

|> request.set_path("/graphql")

|> request.prepend_header("authorization", "bearer " <> gh_token)

|> request.set_body("{ \"query\": \"" <> query <> "\"}")

+ |> httpc.send

}

Here I'm

assert-ing that I will get a response from the server, so this code will crash in case there's an error. For my little application it is completely fine to crash when an error occurs, but most of the times you'd want to actually deal with the error!

The JSON string we get back looks something like this (after being nicely formatted):

{

"query": {

"viewer": {

"pullRequests": {

"nodes": [

{ "mergeable": "CONFLICTING", "isDraft": true, "title": "...", "url": "..." },

{ "mergeable": "MERGEABLE", "isDraft": false, "title": "...", "url": "..." },

{ "mergeable": "UNKNOWN", "isDraft": false, "title": "...", "url": "..." }

]

}

}

}

}

So the first PR has a conflict that needs to be addressed, while the second one

has no issues. The third PR has an "UNKNOWN" status, that means GitHub is

still determining if it can be safely merged or not.

It's pretty straightforward to describe such a PR using a couple of custom types in Gleam:

pub type PullRequest {

PullRequest(

title: String,

url: String,

mergeability: Mergeability,

is_draft: Bool

)

}

pub type Mergeability {

Conflicting

Mergeable

Unknown

}

Dealing with the unknown

The response we get back from the API is a plain string containing an unknown

JSON object. So, before we can do anything meaningful with this data, we need to

parse it into something with a known shape: a list of PullRequests in this

case.

One can do that in Gleam using a

Decoder: a value

that can be used to turn unknown data into well typed values.

The nice thing about decoders is that they can compose nicely, so we can start

with small building blocks and join them together as needed.

Let's start with the decoder for mergeability, those are plain strings in

the JSON response:

import gleam/dynamic/decode.{type Decoder}

pub fn mergeability_decoder() -> Decoder(Mergeability) {

// We first start by trying to decode a string...

use decoded_string <- decode.then(decode.string)

// ... if we could decode it, then we can check if it's one of

// the three expected values:

case decoded_string {

// If it is, we succeed and return the corresponding value.

"CONFLICTING" -> decode.success(Conflicting)

"MERGEABLE" -> decode.success(Mergeable)

"UNKNOWN" -> decode.success(Unknown)

// Otherwise we fail providing an example and a textual

// description of what we were expecting to see.

_ -> decode.failure(Unknown, "Mergeability")

}

}

We can now define a decoder that takes care of decoding a single PR object, by decoding each individual field:

pub fn pull_request_decoder() -> Decoder(PullRequest) {

use title <- decode.field("title", decode.string)

use url <- decode.field("url", decode.string)

// We decode the "mergeable" field by using the decoder we've defined earlier!

use mergeability <- decode.field("mergeable", mergeability_decoder())

use is_draft <- decode.field("isDraft", decode.bool)

// If we can decode all the fields we care about, then we can return a PR!

decode.success(PullRequest(title:, url:, mergeability:, is_draft:))

}

And now everything is ready to decode the full response into a list of pull requests:

import gleam/json

pub fn fetch_pull_requests(gh_token: String) -> List(PullRequest) {

// ...

let response_decoder =

decode.at(

["data", "viewer", "pullRequests", "nodes"],

decode.list(pull_request_decoder())

)

let assert Ok(pull_requests) = json.parse(response.body, response_decoder)

pull_requests

}

Notice how we pieced together the little decoders we defined to get an increasingly more powerful decoder: we start with something that can decode just a mergeability string into a Gleam type, we use it to define something that can decode a single pull request. Finally, we can use that to define a decoder that decodes a list of pull requests that is found deeply nested in a json object.

Now we're just missing a way to nicely display all this data!

Enters the trusty Raspberry Pi Zero

A while ago I got a Raspberry Pi Zero 2 W, a tiny, tiny $15 computer. Being a Gleam nerd, of course I wanted to try and run some Gleam code on it! It was great fun playing around with it and with some little displays I had lying around.

In my DIY hardware era 💅

This is powered by Gleam running on a Raspberry Pi Zero, how cool is that?

In the end I turned it into a small local server that I use to play silly games when my friends come over; and all the code powering it is written in, you guessed it, Gleam. For this I'm using the Wisp framework. The gist of it is you define a handler that, given an HTTP request, produces a response:

// The simplest handler I could think of: always returns a fixed html response.

pub fn handle_request(req: wisp.Request) -> wisp.Response {

"<h1>Hello, Joe!</h1>"

|> wisp.html_response(200)

}

The real deal is actually a bit more complex and will do routing using pattern matching:

pub fn handle_request(req: wisp.Request) -> wisp.Response {

case wisp.path_segments(req) {

[] -> homepage()

["games", "scattergories"] -> scattergories_page(req)

_ -> wisp.not_found()

}

}

So having this already set up, I decided to make it a bit more capable and add a new route to serve a page showing all that useful info gathered from GitHub's API:

pub fn handle_request(

req: wisp.Request,

+ gh_token: String,

) -> wisp.Response {

case wisp.path_segments(req) {

[] -> homepage()

["games", "scattergories"] -> scattergories_page(req)

+ ["git", "pull-requests"] -> pull_requests_page(gh_token)

_ -> wisp.not_found()

}

}

All the hard work of fetching and decoding the pull requests is already

implemented in fetch_pull_requests, so we just need a way to dinamically

produce some HTML document from those.

HTML templating with Lustre

To do that I'm using Lustre, a Gleam web framework for building HTML templates, single page applications, and real-time server components. In my case I'm using it just for the HTML templating, and it looks like this:

import lustre/element/html

pub fn pull_requests_page(gh_token: String) -> Element(msg) {

let pull_requests = fetch_pull_requests(gh_token)

html.main([], [

html.h1([], [html.text("Pull Requests")]),

html.ul([], todo as "the list items")

// ^^^^ A handy Gleam keyword to leave some bits

// and pieces of code unimplemented!

])

}

The thing I love about Lustre is that everything is just functions™️, there's no external templating language, fancy macros, or new syntax I need to learn: all I know about refactoring and organising code applies just as nicely to my HTML-producing code. So here to keep things nice and tidy I want to define a helper function that takes care of turning a single pull request into a list item:

pub fn pull_request_to_li(pull_request: PullRequest) -> Element(msg) {

let mergeability = case pull_request.mergeability {

Mergeable -> "✅"

Conflicting -> "❌"

Unknown -> "⚙️"

}

let draft = case pull_request.is_draft {

True -> " (DRAFT) "

False -> " "

}

html.li([], [

html.text(mergeability <> draft),

html.a([attribute.href(pull_request.url)], [

html.text(pull_request.title),

]),

])

}

That can be reused for all the pull requests in the list we've fetched:

import lustre/element/html

+import gleam/list

pub fn pull_requests_page() {

// In the real code this is read at startup from an env variable,

// never put secrets in your code!

let gh_token = todo as "a GitHub access token"

let pull_requests = fetch_pull_requests(gh_token)

html.main([], [

html.h1([], [html.text("Pull Requests")]),

- html.ul([], todo as "the list items")

+ html.ul([], list.map(pull_requests, pull_request_to_li))

])

}

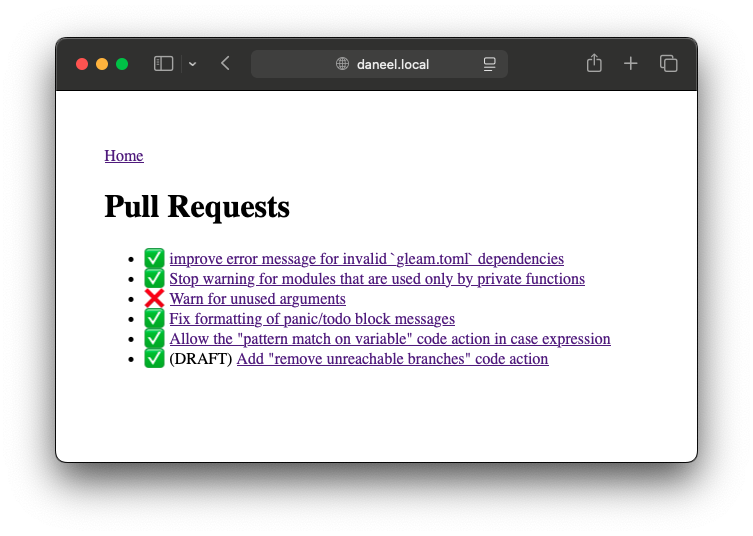

The final result

I set up a systemctl timer – thank you Louis for introducing me to that! –

to fire up the server listening on port 80 every time the Raspberry is turned

on:

pub fn main() -> Nil {

wisp.configure_logger()

// Totally fine to assert here, if those env variables are not set there's no

// way we can try and keep running, so we might as well panic!

let assert Ok(port) = envoy.get("DANEEL_PORT") |> result.try(int.parse)

as "DANEEL_PORT should be set"

let assert Ok(gh_token) = envoy.get("GH_TOKEN")

as "GH_TOKEN should be set"

let assert Ok(_) =

// This is the handler I just showed you!

handle_request(_, gh_token)

|> wisp_mist.handler(wisp.random_string(64))

|> mist.new

|> mist.bind("0.0.0.0")

|> mist.port(port)

|> mist.start

process.sleep_forever()

}

And now I can browse to my Raspberry and see at a glance whether any of my PRs need some fixing, pretty neat if you ask me!

Yes, I know this won't probably win a design award, but I'm quite fond of the web 1.0 aesthetic and that's more than enough for me.

Was it worth it?

We all know the joke of the developer speding months trying to automate a 5 minutes task. But this actually took me less than an hour to build – Gleam is an incredibly productive language!

I think there's something exhilarating in racking one's brain trying to automate routine tasks; and even if this might not have been worth the time, I sure had loads of fun… and that's the whole point of coding!